Carbonyl Compounds

Welcome to Carbonyl Crescent – a small, overachieving street where every resident has a carbonyl group (C=O) in their backbone and far more chemical personality than a plain hydrocarbon. Add C=O to a carbon chain, and you change its polarity, reactivity and how it behaves in plant chemistry, from sharp fruit acids to fragrant esters and sturdy amide links in proteins.

On this page, we’re walking down Carbonyl Crescent to meet the main families you’ll keep seeing in both organic chemistry and herbal medicine: aldehydes (–CHO), ketones (>C=O), carboxylic acids (–COOH), esters (–COOR) and amides (–CONH–). Each retains the same C=O core, but what’s attached to it changes everything, including how it dissolves, how it reacts, and where it appears in herbs, oils, and essential oils.

Aldehyde

Aldehydes – End-of-Terrace Carbonyls (–CHO).

Aldehydes – No. 1 Carbonyl Crescent (–CHO)

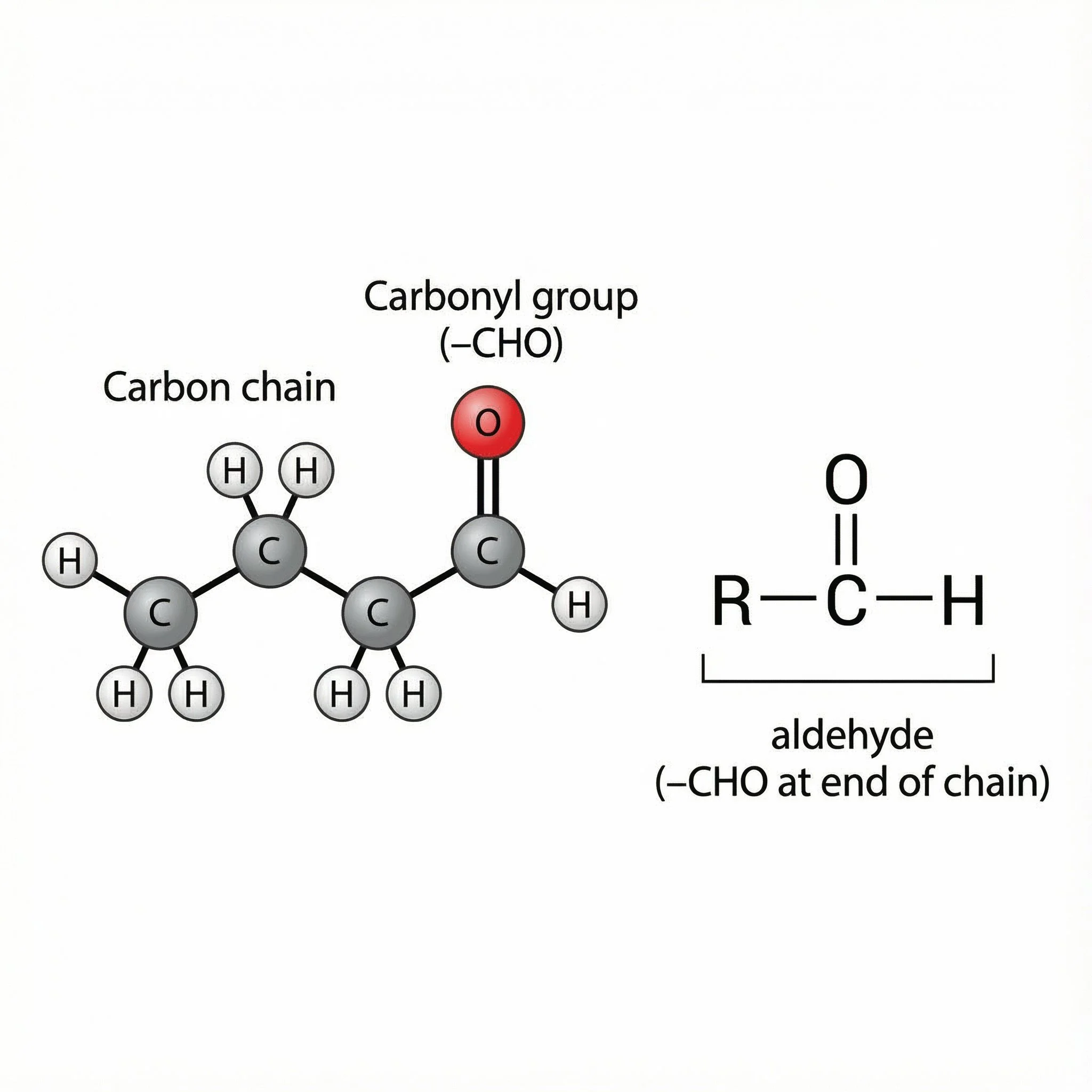

An aldehyde is a carbonyl compound where the C=O group is at the end of a carbon chain, and the carbonyl carbon is bonded to:

one hydrogen, and

one carbon group (R)

General pattern:

R–C(=O)H

often written as –CHO

On Carbonyl Crescent, aldehydes live in the end-of-terrace house at No. 1. That “end-of-terrace” idea is your reminder that:

the carbonyl is at the end of the chain, and

It’s a bit more exposed and reactive than when it’s in the middle (like in a ketone).

The “slightly scruffy” part is the memory hook: an aldehyde is often one oxidation step away from becoming the smarter, more “finished” carboxylic acid on the corner at COOH & Chips.

How to spot an aldehyde

Look for:

A C=O at the end of the molecule

The carbonyl carbon is attached to H on one side and R on the other

A formula or shorthand ending in –CHO

Naming pattern:

Names usually end in “-al”

e.g. methanal, ethanal, propanal, butanal

No. 1 Alde-House, Carbonyl Crescent: The scruffy end-of-terrace aldehyde. The grumpy molecule in the window has a carbonyl (C=O, red and grey) with a single hydrogen (H) and an R group on the same carbon – that makes it an aldehyde (–CHO). It’s literally at the end of the street because aldehydes have their carbonyl at the end of the chain and are more exposed and reactive than ketones. The peeling paint is a reminder that an aldehyde is reactive and only one oxidation step away from saying “f**k it” and going to COOH & Chips down the road and turning into a carboxylic acid (–COOH) for a chippy tea.

What aldehydes do

The main points:

More reactive than ketones

Less crowded around the carbonyl (one side is just H), so reagents can get in more easily.

Easily oxidised to carboxylic acids

Aldehyde → carboxylic acid (e.g. ethanal → ethanoic acid).

This is why classic tests (Tollens’, Fehling’s/ Benedict’s) pick up aldehydes but not ketones.

Can be reduced to primary alcohols

Aldehyde ⇌ primary alcohol (depending on reagents/direction).

Often strong-smelling

Short ones can be pungent; many aromatic/longer aldehydes are key flavour and fragrance molecules.

Aldehydes in plant / herbal chemistry

You’ll meet aldehydes in:

Essential oils and aromas – e.g.

Cinnamaldehyde (cinnamon)

Citral (lemony smell in some citrus and lemongrass)

Vanillin (main aroma of vanilla – an aromatic aldehyde)

They’re usually volatile and reactive, contributing to a herb’s scent, flavour, and sometimes irritant or stimulating effects.

Ketone

Ketone Cottage - C=O in the middle.

Ketone Cottage – C=O in the middle. Our smug-faced neighbour is a ketone: the carbonyl carbon (grey C with red O on top) is bonded to two carbon groups, R and R′, and no hydrogen, so it lives safely in the middle of Carbonyl Crescent. That comfy position is why ketones are more stable and harder to oxidise than the scruffy aldehyde at No. 1, who’s only one step away from moving into COOH & Chips and becoming a carboxylic acid. For revision:

Middle of chain, R–C(=O)–R′ = ketone

Formed from secondary alcohols

Less keen to oxidise than aldehydes, often turning up as aroma molecules in plants and essential oils rather than sour acids.

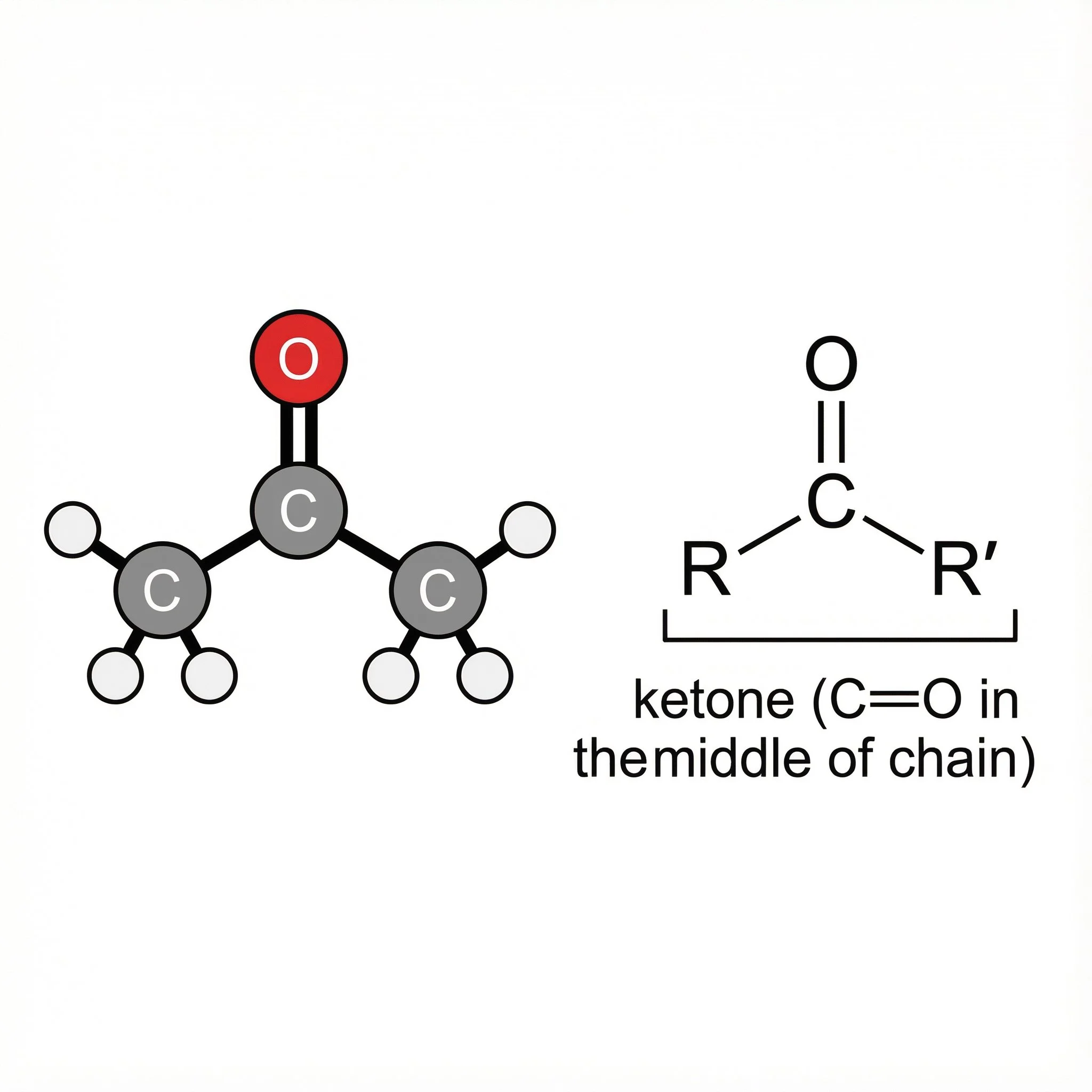

A ketone is a carbonyl compound where the C=O group sits in the middle of a carbon chain. The carbonyl carbon is bonded to:

two carbon groups (R and R′)

no hydrogens on the carbonyl carbon

General pattern:

R–C(=O)–R′ (often written as >C=O)

On Carbonyl Crescent, ketones live in the middle terrace – neighbours (carbons) on both sides, no exposed hydrogen at the end. That’s your visual cue that ketones are:

more “shielded” around the C=O

harder to oxidise than the scruffy aldehyde at No. 1 (–CHO).

Revision bullets points

Spot: C=O in the middle of the chain, attached to two carbons, no –H on that carbon.

Naming: usually ends in “-one” – propanone, butanone, cyclohexanone.

Made from: oxidation of a secondary alcohol.

Reactions: can be reduced back to a secondary alcohol; undergo nucleophilic addition at C=O; don’t oxidise further easily (unlike aldehydes).

Ketones in Herbal Medicine

In plant chemistry, ketones are a diverse bunch. They all share the same core – a carbonyl group in the middle of a carbon chain (R–C(=O)–R′), but their effects range from gentle and aromatic to quite punchy and stimulating.

You’ll most often meet ketones in:

Essential oils and volatile fractions

– e.g. camphor (from Cinnamomum camphora), carvone (caraway, spearmint), menthone (mints), and thujone (sage, some Artemisias).

– These contribute to the characteristic scent of many herbs, minty, camphoraceous, “nose-opening” aromas.Flavour compounds

– Some ketones help create spicy, herbal and minty flavours, shaping a herb’s overall sensory profile and how people experience the remedy.

From a herbalist’s point of view, ketones tend to be:

Volatile and lipophilic: more at home in essential oils, inhalations and aromatic rubs than in simple watery infusions.

Often stimulating or clearing in feel: think “opens the head and sinuses”, “sharp, penetrating smell”.

Sometimes dose-sensitive: a few ketone-rich essential oils are linked with neurotoxic or convulsant risks in high doses, so they’re used carefully and in small amounts.

And do they react? Yes, but in a calmer, more refined manner than aldehydes. The carbonyl in a ketone is still polar, so that the carbonyl carbon can take part in nucleophilic addition and reduction reactions, and it can be reduced back to a secondary alcohol. But with carbon neighbours on both sides and no hydrogen on the carbonyl carbon, ketones are less exposed and more challenging to oxidise than the scruffy aldehyde at No. 1 Carbonyl Crescent. They still “do chemistry”; they don’t rush off to COOH & Chips at the first sign of an oxidising agent.

Carboxylic acids

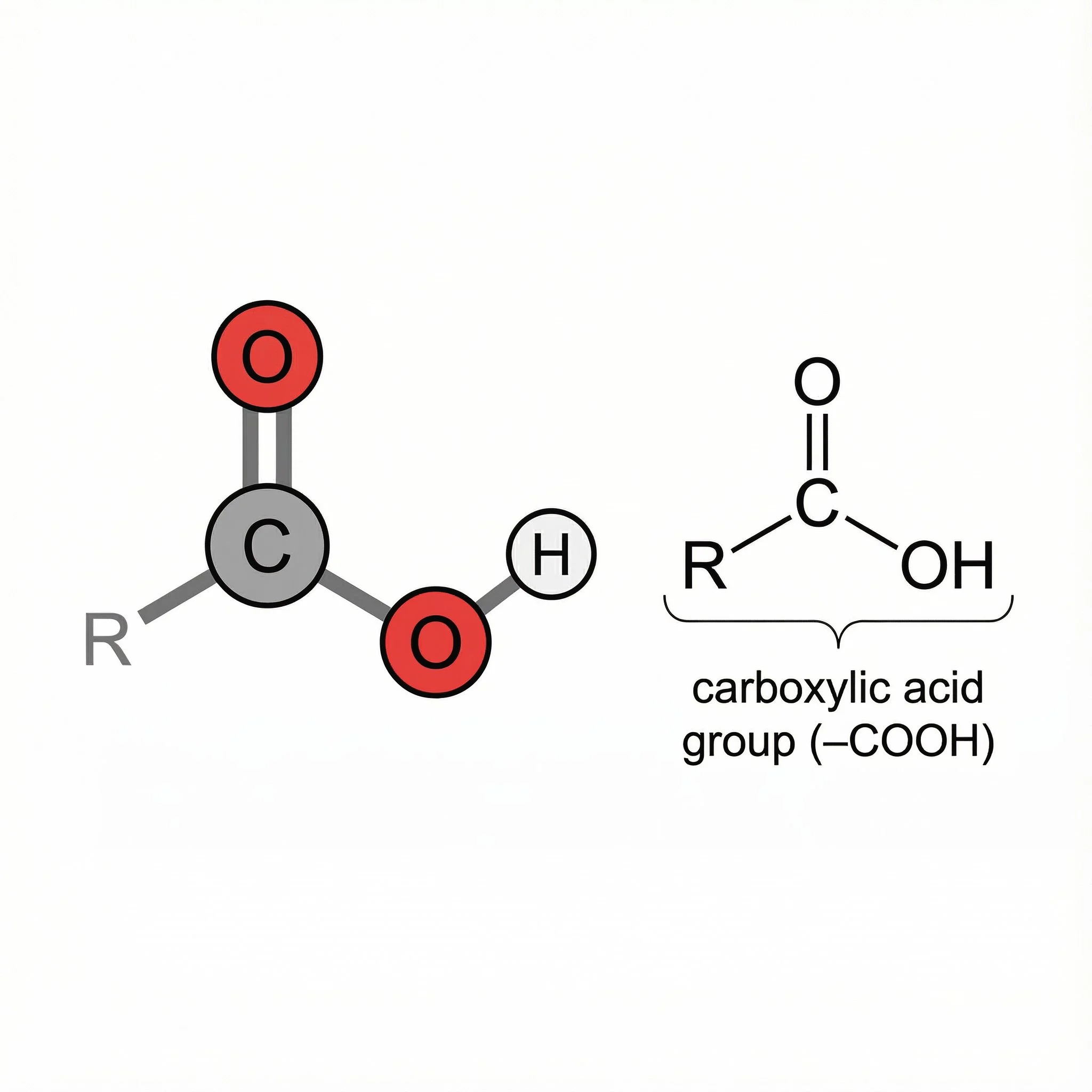

Carboxylic acids are molecules with the –COOH functional group, a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) attached to the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. This arrangement makes them genuinely acidic and highly polar, so they often contribute sharp, tangy flavours and good water solubility in plant chemistry, from fruit acids such as citric and malic, to lactic acid and long-chain fatty acids in herbal oils.

COOH and Chips.

COOH & Chips – our carboxylic acid mascot in his natural habitat. The –COOH on his belly is the carboxylic acid group: a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) on the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. In the chip shop, you meet it as ethanoic acid in the vinegar on your chips, citric acid in the lemon squeezed over the fish, and in the frying oil, where long-chain fatty acids are just carboxylic acids with very long hydrocarbon tails.

Carboxylic Acids - COOH and CHIPS.

I have used the “COOH and CHIPS” shop as a study aid of carboxylic acids: ethanoic acid in vinegar on chips, citric acid in the lemon squeezed over fish, and long-chain fatty acids in the frying oil. Your COOH & Chips mascot is a reminder that all of these share the same –COOH “heart”, even though their chains and behaviour differ.

Carboxylic acids are molecules with the –COOH functional group – a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) attached to the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. This arrangement makes them weak organic acids that are usually relatively polar and often sour-tasting.

In herbal medicine, the same family shows up as fruit acids (citric, malic, tartaric), lactic acid in fermented preparations, and fatty acids in herbal oils and balms. They help shape a remedy’s taste (e.g., sharp, tangy), water solubility, tissue interactions, and skin-barrier effects, making the –COOH group an important part of a herb’s overall chemical character.

A closer look at –COOH.

The –COOH group has two highly electronegative oxygen atoms attached to a carbon atom, so they draw electron density toward themselves. This makes the O–H bond in –COOH easier to break, so the group can lose a proton (H⁺) and behave as an acid. When the proton is lost, you get –COO⁻, and the negative charge is shared between the two oxygens – this helps to stabilise the ion and makes carboxylic acids more acidic than alcohols. The –COOH group is also polar and can form hydrogen bonds, which gives small carboxylic acids relatively high boiling points and good solubility in water. In herbal chemistry, polarity and acidity help explain why fruit and phenolic acids readily extract into teas and tinctures, whereas fatty acids behave differently in oils and on the skin.

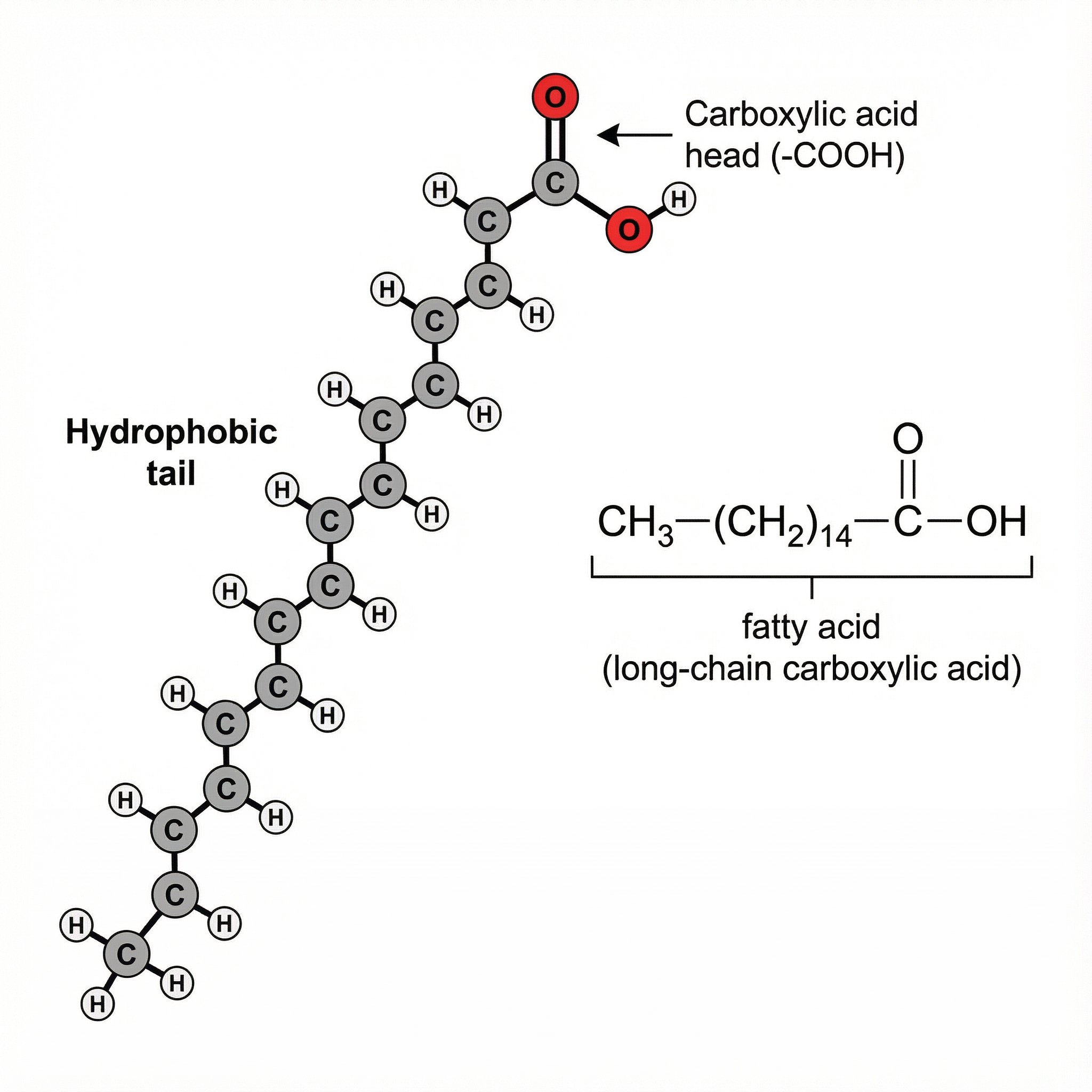

Fatty Acids – Long-Tailed Carboxylic Acids

Fatty acids are basically carboxylic acids with a long hydrocarbon tail. Chemically, they still have the same –COOH group at one end, but instead of a tiny R group, they’ve got a long chain of carbons and hydrogens:

R–C(=O)–OH, where R is a long carbon chain (often C₁₂–C₂₂ or more).

At one end, you’ve got the polar, acidic –COOH “head”, and at the other a non-polar, oily “tail”. That mix renders fatty acids amphipathic; one end prefers water, whereas the rest interacts with oils and membranes.

You’ll see them described as:

Saturated: no C=C double bonds, straight tails, pack tightly (e.g. stearic acid).

Unsaturated: one or more C=C double bonds, kinked tails, more fluid (e.g. oleic, linoleic).

Fatty acids, COOH & the chip shop link

In the COOH & Chips world, fatty acids are the ones hiding in the frying oil: still carboxylic acids, just with very long tails. The –COOH head is the same as the fella in the chip shop, but most of the molecule is a greasy hydrocarbon chain.

That’s why:

They don’t dissolve in water (the tail dominates),

But they mix beautifully with oils, membranes and skin,

And form the basis of triglycerides (three fatty acids + glycerol).

Why fatty acids matter in herbal medicine

From a herbalist’s point of view, fatty acids are essential because they:

Make up the fixed oils in seeds and nuts (e.g. evening primrose, flax, sunflower).

Contribute to skin-barrier repair and emollient effects in creams, balms and infused oils.

Affect inflammation and cell signalling (especially essential fatty acids like omega-3 and omega-6).

Explain why some constituents only really show up in oil-based preparations (infused oils, ointments) rather than teas and tinctures.

So:

Same –COOH family,

But with a long hydrophobic tail that pulls them into the world of oils, membranes and skin medicine, rather than your teapot.

Ester

Carboxylic acids are molecules with the –COOH functional group, a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) attached to the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. This arrangement makes them genuinely acidic and highly polar, so they often contribute sharp, tangy flavours and good water solubility in plant chemistry, from fruit acids such as citric and malic, to lactic acid and long-chain fatty acids in herbal oils.

Ester.

COOH & Chips – our carboxylic acid mascot in his natural habitat. The –COOH on his belly is the carboxylic acid group: a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) on the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. In the chip shop, you meet it as ethanoic acid in the vinegar on your chips, citric acid in the lemon squeezed over the fish, and in the frying oil, where long-chain fatty acids are just carboxylic acids with very long hydrocarbon tails.

Carboxylic Acids - COOH and CHIPS.

I have used the “COOH and CHIPS” shop as a study aid of carboxylic acids: ethanoic acid in vinegar on chips, citric acid in the lemon squeezed over fish, and long-chain fatty acids in the frying oil. Your COOH & Chips mascot is a reminder that all of these share the same –COOH “heart”, even though their chains and behaviour differ.

Carboxylic acids are molecules with the –COOH functional group – a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) attached to the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. This arrangement makes them weak organic acids that are usually relatively polar and often sour-tasting.

In herbal medicine, the same family shows up as fruit acids (citric, malic, tartaric), lactic acid in fermented preparations, and fatty acids in herbal oils and balms. They help shape a remedy’s taste (e.g., sharp, tangy), water solubility, tissue interactions, and skin-barrier effects, making the –COOH group an important part of a herb’s overall chemical character.

A closer look at –COOH.

The –COOH group has two highly electronegative oxygen atoms attached to a carbon atom, so they draw electron density toward themselves. This makes the O–H bond in –COOH easier to break, so the group can lose a proton (H⁺) and behave as an acid. When the proton is lost, you get –COO⁻, and the negative charge is shared between the two oxygens – this helps to stabilise the ion and makes carboxylic acids more acidic than alcohols. The –COOH group is also polar and can form hydrogen bonds, which gives small carboxylic acids relatively high boiling points and good solubility in water. In herbal chemistry, polarity and acidity help explain why fruit and phenolic acids readily extract into teas and tinctures, whereas fatty acids behave differently in oils and on the skin.

Amide

Carboxylic acids are molecules with the –COOH functional group, a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) attached to the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. This arrangement makes them genuinely acidic and highly polar, so they often contribute sharp, tangy flavours and good water solubility in plant chemistry, from fruit acids such as citric and malic, to lactic acid and long-chain fatty acids in herbal oils.

Amide.

COOH & Chips – our carboxylic acid mascot in his natural habitat. The –COOH on his belly is the carboxylic acid group: a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) on the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. In the chip shop, you meet it as ethanoic acid in the vinegar on your chips, citric acid in the lemon squeezed over the fish, and in the frying oil, where long-chain fatty acids are just carboxylic acids with very long hydrocarbon tails.

Carboxylic Acids - COOH and CHIPS.

I have used the “COOH and CHIPS” shop as a study aid of carboxylic acids: ethanoic acid in vinegar on chips, citric acid in the lemon squeezed over fish, and long-chain fatty acids in the frying oil. Your COOH & Chips mascot is a reminder that all of these share the same –COOH “heart”, even though their chains and behaviour differ.

Carboxylic acids are molecules with the –COOH functional group – a carbonyl (C=O) and a hydroxyl (O–H) attached to the same carbon, written R–C(=O)–OH. This arrangement makes them weak organic acids that are usually relatively polar and often sour-tasting.

In herbal medicine, the same family shows up as fruit acids (citric, malic, tartaric), lactic acid in fermented preparations, and fatty acids in herbal oils and balms. They help shape a remedy’s taste (e.g., sharp, tangy), water solubility, tissue interactions, and skin-barrier effects, making the –COOH group an important part of a herb’s overall chemical character.

A closer look at –COOH.

The –COOH group has two highly electronegative oxygen atoms attached to a carbon atom, so they draw electron density toward themselves. This makes the O–H bond in –COOH easier to break, so the group can lose a proton (H⁺) and behave as an acid. When the proton is lost, you get –COO⁻, and the negative charge is shared between the two oxygens – this helps to stabilise the ion and makes carboxylic acids more acidic than alcohols. The –COOH group is also polar and can form hydrogen bonds, which gives small carboxylic acids relatively high boiling points and good solubility in water. In herbal chemistry, polarity and acidity help explain why fruit and phenolic acids readily extract into teas and tinctures, whereas fatty acids behave differently in oils and on the skin.

Sources

Berg, J. M., Tymoczko, J. L., Gatto, G. J., Jr., & Stryer, L. (2019). *Biochemistry* (9th ed.). W. H. Freeman.

Bone, K., & Mills, S. (2013). *Principles and practice of phytotherapy: Modern herbal medicine* (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

CGP Books. (2021). *A-Level chemistry: Complete revision & practice (with online edition).* Coordination Group Publications.

McIntyre, A. (2019). *The complete herbal tutor: The definitive guide to the principles and practices of herbal medicine* (Rev. & expanded ed.). Aeon Books.

McMurry, J. E. (2016). *Organic chemistry* (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.